Does your Primary 4 child struggle with math problem sums?

You’re not alone. Many parents notice their children hitting a wall when they reach P4 math – and there’s a good reason why. Primary 4 marks a significant jump in difficulty, with more complex heuristics, abstract thinking, and multi-step problem-solving that can leave even bright students feeling overwhelmed.

The challenge is real. P4 math problem sums introduce concepts like model drawing with fractions, before-and-after scenarios, and assumption methods that require a completely different approach from the straightforward calculations your child mastered in lower primary.

But here’s the good news: once you understand why these problems are tricky, they become much more manageable.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll walk through 8 of the most challenging P4 math problem sums that frequently appear in school tests and PSLE preparation. More importantly, we’ll explain exactly why each question trips up students and provide clear, step-by-step solutions that you can use to guide your child.

Whether your child is preparing for upcoming exams or you want to strengthen their problem-solving foundation, these worked examples will help you both tackle P4 math with confidence.

Before you read on, you might want to download this entire revision notes in PDF format to print it out, or to read it later.

This will be delivered to your email inbox.

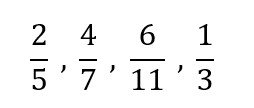

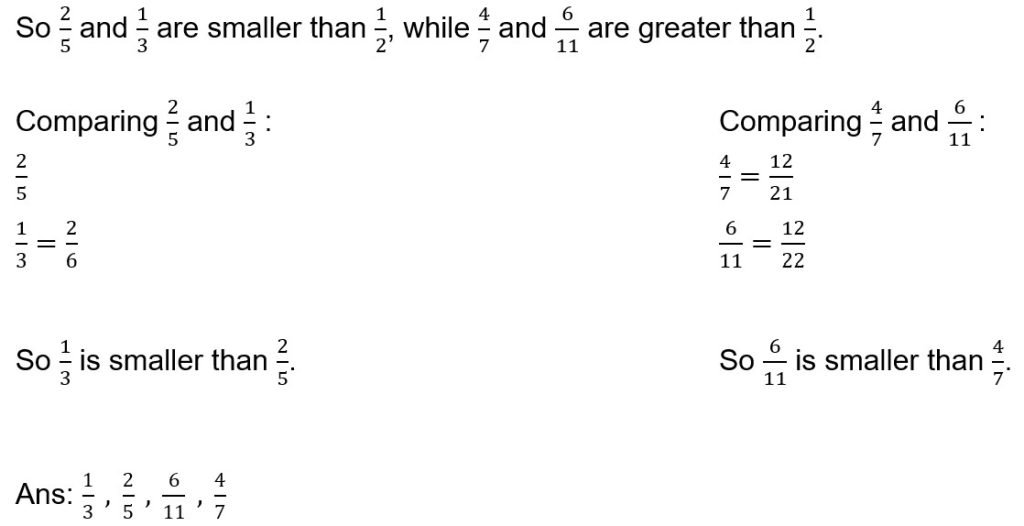

Q1 − Comparing and Ordering Unlike Fractions

Arrange the following fractions from the smallest to the largest.

Solution:

Observe:

Half of 5 = 2.5, half of 7 = 3.5, half of 11 = 5.5 and half of 3 = 1.5

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

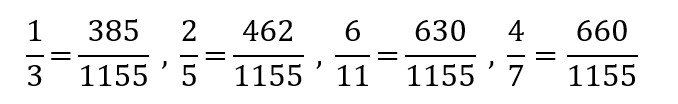

There are different approaches to comparing the given fractions. The most common and most direct method would be to express all fractions into the same common denominator and then compare the numerator. By using this method, they need to obtain:

The process of obtaining the fractions above would be difficult and exhausting for some primary 4 students since it requires students to predetermine the Lowest Common Multiple (LCM − 1155) of 4 numbers and conversions involve many steps of multiplication. This would then increase the chance of making careless mistakes in their calculations. In addition, this method would use up too much time.

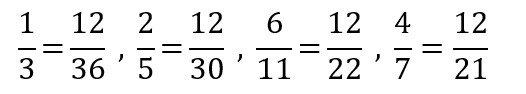

The other method they are taught would be to compare the denominators when the fractions have the same numerator. By using this method, they need to obtain:

This would also require students to obtain the LCM of four numbers. Although the LCM here is smaller (36) compared to the previous LCM (1155), some students may still struggle.

In addition, comparing fractions with the same numerator by looking at denominators can be tricky because it goes against their earlier intuition about numbers. Students are used to thinking that “a bigger number means more”. So, when they see denominators like 5 and 7, they may think that a fraction with denominator 7 is larger because 7 is bigger than 5.

Since the denominator shows how many equal parts the whole is divided into, a larger denominator means smaller parts. This idea is abstract, and students need to imagine dividing a whole into more pieces, which makes each piece smaller. This visualisation is often difficult for weaker students without concrete aids like fraction bars or circles.

When numerators are the same, the fraction with the smaller denominator is bigger. But when denominators are the same, the fraction with the bigger numerator is bigger. This switch in rules can confuse some students because it requires flexible thinking.

The suggested solution also incorporates a third method of comparing against 1/2. By separating the given fractions into two groups, this can “lighten” the burden of working with four unlike fractions at once. However, students who are weak in mental sums or fraction concepts may not be able to apply this. For example, they may not see that 6/11 is more than 1/2 because it requires noticing that half of 11 is 5.5, which is greater than 6.

Q2 − Model Drawing (Completing Unit)

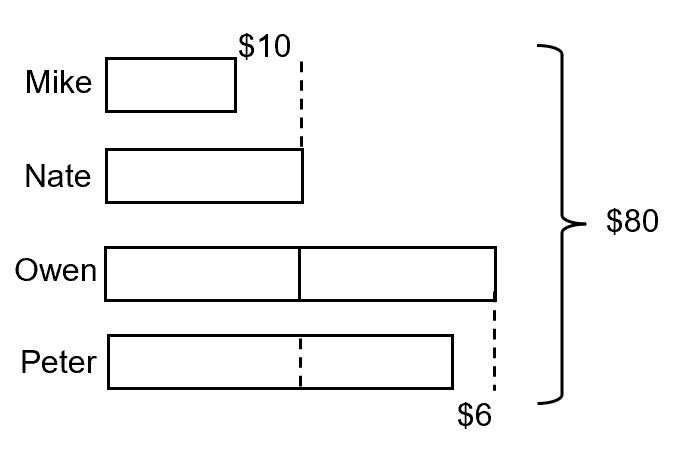

Four boys received a sum of money. Mike received $10 less than Nate. Owen received twice as much money as Nate. Peter received $6 less than Owen. The four boys received $80 in total. How much money did Peter receive?

Solution:

We need to add $10 to Mike so that his bar becomes a complete unit.

We need to add $6 to Peter so that his bar becomes two complete units.

$80 + $10 + $6 = $72

6 units = $96

1 unit = $96 ÷ 6 = $16

Peter has $6 less than 2 units.

2 units = $16 × 2 = $32

Amount received by Peter = $32 – $6 = $26 (ans)

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

Note: A common error for pupils in this question would be to subtract $10 and $6 from $80. Then equate the value to 6 units.

This is wrong because Peter is actually short of $6 to form 2 complete units. And Mike is short of $10 to form a complete unit.

Subtracting $6 from Peter would not enable him to form 2 units. And subtracting $10 from Mike would also not enable him to form 1 complete unit.

The correct method would be to add $6 and $10 to the total as shown in the solution.

This common error is made because pupils are too used to subtracting extra parts to make complete units when first learning model drawing. See example below.

Mike and Nate shared a sum of $80. Nate received $10 more than Mike. How much money did Mike receive?

Solution:

In the example above, we would subtract $10 from the big total and then equate 2 units to $70.

$80 − $10 = $70

2 units = $70

1 unit = $70 ÷ 2 = $35 (ans)

Q3 − Before-and-After Model Drawing (“Unseen” Units)

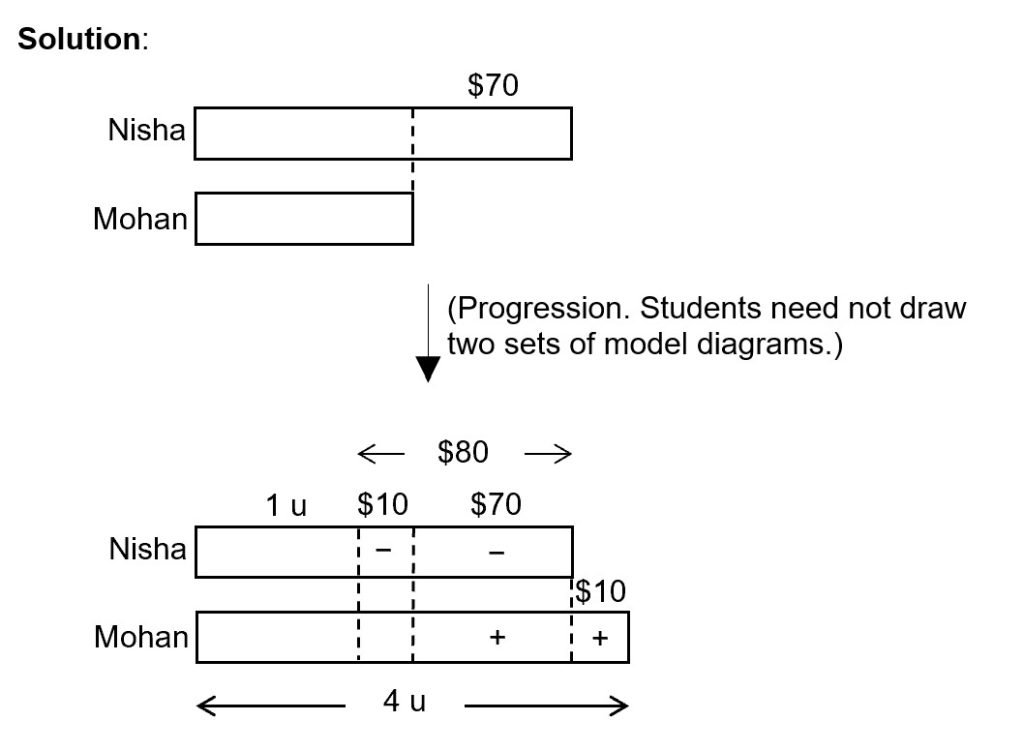

Nisha had $70 more than Mohan. After she gave $80 to Mohan, Mohan had four times as much money as Nisha. How much money did they have altogether?

Given in the end, Mohan would have 4 units and Nisha would have 1 unit. Since Mohan had $90 more than Nisha. So we can equate 3 units to $90.

$80 + $10 = $90

3 units = $90

1 unit = $90 ÷ 3 = $30

Total number of units = 5 units.

5 units = $30 × 5 = $150 (ans)

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

It was given Nisha had $70 more than Mohan. But she would give him $80. When representing this change in model diagram, some pupils might find it challenging and not recognise that the final difference between Nisha and Mohan was actually $90.

Furthermore, pupils would have to know that the entire bar for Mohan in the end would have a value of 4 units even though the bar was not divided equally into 4 equal parts. Some students might struggle to make this connection without “seeing” 4 equal units.

Q4 − Area and Perimeter (Identify Relationship Between Length and Breadth)

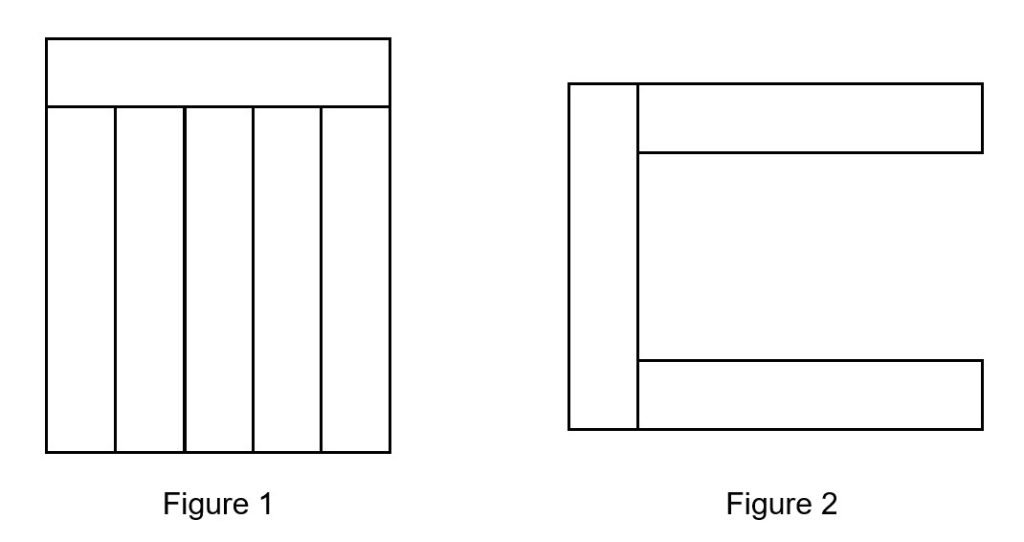

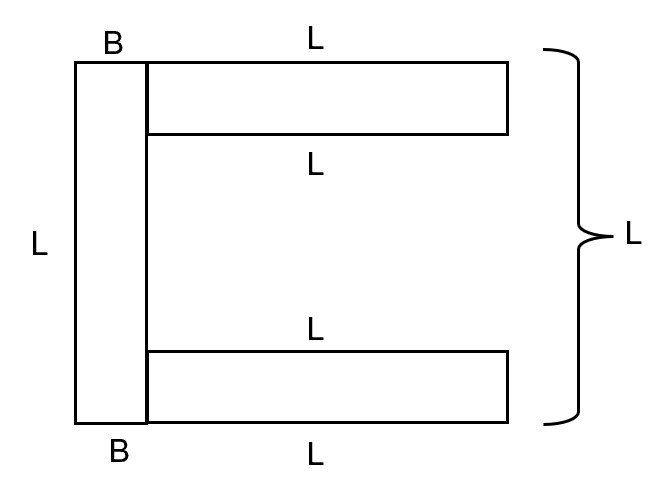

Identical rectangles are arranged form shapes as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The perimeter of the shape in Figure 2 is 96 cm. What is the area of the shape in Figure 1?

Solution:

In Figure 1, see that the length of the rectangle is 5 times the breadth.

The perimeter of the shape in Figure 2 is made up of 6 lengths and 2 breadths.

Since 1 L is equivalent to 5 B,

6 L is equivalent to 30 B.

The perimeter of the shape in Figure 2 is made up of 30B + 2B = 32 B

32B = 96 cm

1B = 3 cm

So 1L = 5 × 3 cm = 15 cm

Area of one rectangle = 15 cm × 3 cm = 45 cm2

Total area of shape in Figure 1 = 6 × 45 cm2 = 270 cm2 (ans)

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

Students need to recognise that Figures 1 and 2 are both built from identical rectangles. They must “see” that the arrangement in Figure 1 shows the length is 5 times the breadth. This requires strong spatial awareness, which not all P4 students have developed yet.

The solution also depends on connecting two shapes: Figure 2 gives the perimeter information while Figure 1 requires the area.

Many P4 students struggle to transfer information from one figure to another when the question does not explicitly state the link.

The solution uses reasoning like:

“Perimeter of Figure 2 = 6L + 2B = 32B” (since 1L = 5B).

This is essentially algebraic substitution, but done without symbols.

P4 students are not yet taught algebra, so this form of proportional reasoning feels abstract and difficult.

In addition, the question asks about area but gives perimeter.

Switching between perimeter and area formulas is conceptually hard at P4, as many students tend to apply the wrong formula when both appear in the same problem.

Q5. − Model Drawing for Fractions with Different Denominators

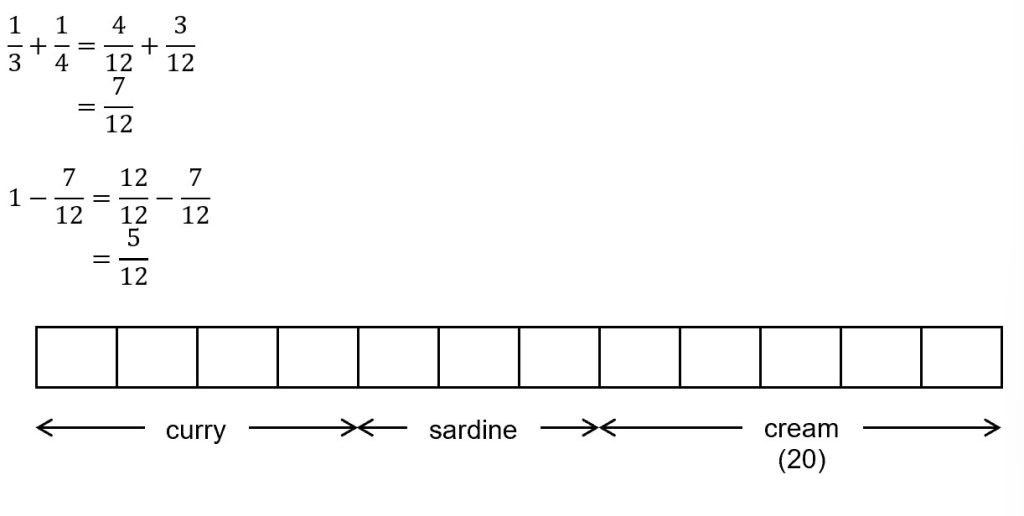

Some snacks were catered for a group of students. 1/3 of the snacks were curry puffs, 1/4 of the snacks were sardine puffs and the rest were cream puffs. If there were 20 cream puffs, how many sardine puffs were catered?

Solution:

5 units = 20

1 unit = 20 ÷ 5 = 4

4 units = 4 × 4 = 16 (ans)

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

This question tests on the concept of Fraction of a Set.

When we say “1/3 of the snacks were curry puffs,” it means the student must picture the whole set of snacks divided into 3 equal groups, with 1 group being curry puffs.

This is the skill of finding a fraction of a quantity, which is introduced in Primary 4.

The difficulty of this question is further increased when the question also gives “1/4 of the snacks were sardine puffs”. Now students must picture the same set of snacks divided into 4 equal groups, which 1 group being sardine puffs.

Many students would start to struggle with this because they cannot “picture” how a group of objects being divided into 3 groups and 4 groups at the same time.

This is especially more challenging if students are weak in the fraction concept of common denominator and equivalent fractions.

While many P4 students can handle the basic concept such as “1/3 of 24” (direct fraction of a set), they must work backwards in this particular question:

“5/12 of the set = 20. What is the whole set? And then what is 1/4 of it?”

This requires flexible use of Fraction of a Set in both directions:

- Fraction × Whole → Part (forward use).

- Given the value of part to find whole or other combined parts (reverse use).

That “reverse” thinking is significantly harder and not fully secure for some P4 students.

Q6. − Excess and Shortage (Fixed Containers)

Mrs Devi bought some pencils for her pupils. If she gives 10 pencils to each pupil, there will be a shortage of 70 pencils. If she gives 5 pencils to each pupil, there will be 105 pencils left. How many pupils are there in Mrs Devi’s class?

Solution:

The number of pupils in the class is fixed, regardless of the number of pencils each pupil receives.

Start with the smaller distribution. After giving 5 pencils to each pupil, there is a leftover of 105.

Now each pupil already has 5 pencils. To give 10 pencils to each pupil, each pupil simply takes 5 more from the leftover of 105. This results in a shortage of 70.

After the second distribution, see that when each pupil takes 5 pencils, 105 + 70 = 175 pencils are required.

Total no. of pupils = 175 ÷ 5 = 35 (ans)

This question can also be solved using Listing Method but it will take up more time.

| 5 pencils for each pupil | 10 pencils for each pupil |

| 5 × 1 pupil + 105 left over = 110 pencils 5 × 2 pupils + 105 left over = 115 pencils 5 × 3 pupils + 105 left over = 120 pencils … 5 × 35 pupils + 105 left over = 280 pencils |

10 × 8 pupil – 70 left over = 10 pencils 10 × 9 pupils – 70 left over = 20 pencils 10 × 10 pupils – 70 left over = 30 pencils … 10 × 35 pupils – 70 left over = 280 pencils |

Ans: 35 pupils

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

This type of “excess and shortage” problem can be difficult because it requires students to connect two different situations at once.

Students may not immediately see that the number of pupils stays the same whether pencils are shared in 5s or 10s. Many focus only on the numbers given (70, 105, 5, 10) and miss this important idea.

When they read “shortage of 70” or “leftover of 105”, weaker students may confuse the two, thinking both mean “not enough” or both mean “extra”. They may not link these terms back to whether there are more pencils than needed, or fewer pencils than needed.

The key step is to realise that the difference between shortage and leftover (70 + 105 = 175) represents the total number of pencils that match the difference in allocation (10 – 5 = 5 pencils per pupil). This connection is not obvious to many students and requires more advanced logical thinking.

The solution relies on reasoning that “5 pencils per pupil × number of pupils = 175”. This is a proportional relationship, which is a higher-order skill that some Primary 4 students have not yet fully developed.

Alternative methods may overwhelm

Students who are not confident may try listing possibilities one by one (the listing method). While straightforward, it is very tedious and time-consuming. On the other hand, the faster solution can feel abstract without strong guidance on the “excess and shortage” heuristic.

Q7. − Constant Difference (Age Gap)

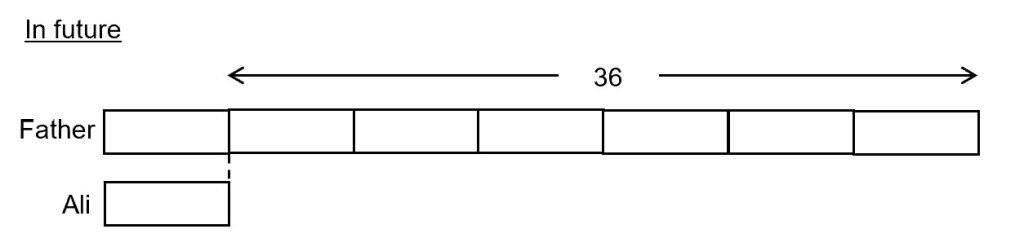

Ali is 12 years old this year and his father is 4 times as old as him. When Ali’s father is/was exactly 7 times Ali’s age, how old is/was Ali and his father?

Solution:

Age of father = 12 × 4 = 48 years old

Age gap between father and Ali = 48 − 12 = 36 years

6 units = 36 years

1 unit = 36 ÷ 6 = 6 years

7 units = 7 × 6 = 42 years

Ans: Ali − 6 years old, Father − 42 years old.

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

Students may mix up “4 times as old” with “4 years older”. Understanding that it means multiplying the age, not just adding, can be difficult. They may also not understand why the father’s age can be 4 times of Ali’s age and be 7 times of Ali’s age in another instance.

The solution relies on realising that the difference in age between father and son stays the same every year. Many students think the gap grows as both get older, which leads to mistakes.

The question asks when the father “is/was” 7 times Ali’s age. Students need to figure out if this happened in the past or will happen in the future. This timeline thinking can be confusing.

To solve it, students must:

(i) Work out the father’s age now,

(ii) Find the age gap,

(iii) Use the “7 times” relationship,

(iv) And finally, find Ali’s age and his father’s age.

Because it involves two timelines, weaker students may also lose track of unit values across different timelines, and which numbers belong to whom.

Q8. − Assumption

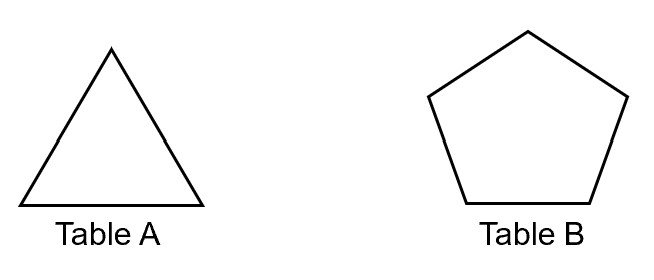

A classroom has two types of tables − A and B.

Table A sits 3 pupils and Table B sits 5 pupils. There are 10 tables, and all 42 pupils are seated at the tables with no seats unoccupied. How many Table Bs are there in the classroom?

Solution:

Assume all 10 tables are Table A.

Total number of seats for Table A = 10 × 3 = 30

There is a shortage of 42 − 30 = 12 seats

Replace one Table A with one Table B, we increase the total number of seats by 5 − 3 = 2 seats

To remove the shortage of 12 seats, we need to do 12 ÷ 2 = 6 replacements.

So there are 6 table Bs. (ans)

Why might this question be challenging for some Primary 4 students?

This problem is tricky because it uses a method that is not obvious and unusual to many students. Students are asked to start by assuming all the tables are the same type. For many, this feels like guessing, and they may not understand why they should do it.

They must realise that the shortage of 12 seats can be removed by replacing smaller tables with bigger ones. Linking a “shortage” to the effect of each replacement is abstract, and some students cannot see this connection clearly.

The solution requires several steps:

(i) Assume all the tables are of a certain type,

(ii) Work out the total shortage,

(iii) Work out how many seats each replacement adds,

(iv) Then divide to find how many replacements are needed.

Students who are not sure of how the replacement step works may lose track along the way.

They may also be unsure of which type of table to assume for all at the start of the solution. Note that when they assume all tables are Table B at the start of the solution, they will be dealing with an excess instead of a shortage of seats.

And because there are two different kinds of tables, some students can mix them up amid their workings.

Before you go, you might want to download this entire revision notes in PDF format to print it out, or to read it later.

This will be delivered to your email inbox.

Does your child need more help?

Find out more about our Math Tuition Class.

1) Live Zoom Lessons at Grade Solution Learning Centre

At Grade Solution Learning Centre, we are a team of dedicated educators whose mission is to guide your child to academic success. Here are the services we provide:

– Live Zoom lessons

– Adaptably, a smart learning platform that tracks your child’s progress, strengths and weaknesses through personalised digital questions.

– 24/7 Homework Helper Service

We provide all these services above at a very affordable monthly fee to allow as many students as possible to access such learning opportunities.

We specialise in English, Math, Science, and Chinese subjects.

You can see our fees and schedules here >>

2) Pre-recorded Online courses on Jimmymaths.com

If you are looking for something that fits your budget, or prefer your child learn at his or her own pace, you can join our pre-recorded online Math courses. This will help your child as they will go beyond simply practising with past exam papers and revise more effectively.

Your child can:

– Learn from recorded videos

– Get access to lots of common exam questions to ensure sufficient practice

– Get unlimited support and homework help

You can see the available courses here >>